It oozes with gothic. There’s a romance to it that lingers. It’s bittersweet, with its melancholy and catharsis. It sinks its maws into you and refuses to let go.

This review contains many spoilers. Content Warnings for Hungerstone: Blood, Gore, Murder, Attempted Murder, Sex-On-Page, Disordered Eating, Gaslighting

‘For what do you hunger?’

But as the couple travel through the bleak countryside, a shocking carriage accident brings the mysterious Carmilla into Lenore’s life. Carmilla, who is weak and pale during the day but vibrant at night, Carmilla who stirs up something deep within Lenore. And before long, girls from the local villages fall sick, consumed by a terrible hunger . . .

As the day of the hunt draws closer, Lenore begins to unravel, questioning the role she has been playing all these years. Torn between regaining her husband’s affection and the cravings Carmilla has awakened, soon Lenore will uncover a darkness in her household that will place her at terrible risk . . .Set against the violent wilderness of the Peaks and the uncontrolled appetite of the Industrial Revolution, Hungerstone is a compulsive sapphic reworking of Carmilla, the book that inspired Dracula: a captivating story of appetite and desire.

Before I begin, I want to extend my thanks to EJ for allowing me to write another guest review and supplying me with the ARC copy of Hungerstone. My vampire obsession is back in full force. To be in her orbit is to be inspired: to write, read, devour fiction. My previous guest review was for Cresent City 2 by Sarah J Maas, where I had some particular opinions.

THE SETTING

‘It is not the dead you should fear.’ The phrase comes as a herald, a warning to the reader, supplying foreshadowing that helps enrich the experience of the book. Straight out of the gate, the book starts with blood. Images of Dracula and the theatrics of vampires immediately come to mind, only to be subverted and reframed into the feminine.

The book starts with Lenore, a thirty-year-old woman lamenting another cycle of menstruation. By the start of the book, her decade–long marriage has soured, the marital bed having been cold for quite some time. She resents her body for not giving her a child and blames that for her estrangement from her husband, Henry. The section ends: ‘I am good for nothing but blood.’ This line stings and lingers, setting up the expectation of Lenore being fed from.

Very rapidly, we leave London to the moors of Yorkshire. The vast green spaces and bracing winds invoke the gothic reminiscent of Wuthering Heights. It doesn’t go unnoticed that both books are set in Yorkshire.

Yorkshire is where we remain for the rest of the book. London only served to emphasise Lenore’s discomfort with her new surroundings once they move into the new house, Nethershaw. The move is to further Henry’s ambition as a steelworks’ owner. He impresses on her the need to have the house presentable for a party they’ll be hosting in the coming weeks.

The book starts the same way as its forebearer: Carmilla comes to the house having taken ill, so the house staff, and by extension, Lenore, have to take care of her. This gives Carmilla the opportunity to prey on members of the household.

Relationship to Carmilla (1872) by Sheridan Le Fau

In Sheridan Le Fau’s original Carmilla (1872), Laura, our main character, recounts the events of the story as they happened 12 years previously when Laura was fifteen or sixteen. In Hungerstone, Lenore is 30 years old, and the events happen to her in ‘real time.’

This means that there’s a more complex perspective in Hungerstone. Lenore’s issues are more visceral and urgent, whereas Laura is more carefree as a young girl. On page 14, ‘The dream comes like an oil slick,’ an image that reminded me of the illustration from The Dark Blue by D. H. Friston, 1872. Carmilla reaches out to prey on Laura, with her father in the background embodying Victorian anxieties of the Other.

TONE

‘Wouldst thou like to live deliciously?’ This is the perfect quote to open the book with, taken from the film The Witch (2015). I think the quote is to be taken at face value in the context of the characters in the book, particularly Carmilla and how she’s able to influence Lenore.

The book is written with the austere tone of a book set in Victorian times, but the language used is modern, allowing it to be more accessible to today’s audience. Le Fau’s Carmilla is quite stuffy and hard to access.

However, the tone shifts as Lenore grows in curiosity and her world-view changes. It loses its austerity, and other emotions are allowed to seep in, like morbidity, panic, desire. It’s a deliciously sapphic, gothic novel.

CHARACTERS

For the most part, there are only five main characters in this book; all other characters are simply on the periphery. They are Lenore, Carmilla, Cora, Henry and Aunt Daphne.

Lenore, as you’d expect, is the character that undertakes the largest metamorphosis. A perfect wife and the perfect image of Victorian societal expectation and propriety, she then goes on a journey of self-discovery and self-actualisation. I discuss her journey throughout this review, so I shan’t linger here.

Oh, Carmilla, you would have loved Chappell Roan. Arguably, the plot doesn’t start until Lenore and Henry recover Carmilla from a carriage crash on the moors on the way to Nethershaw. Carmilla and Lenore’s relationship is a driving catalyst throughout the book.

Carmilla is the most sumptuous character in the book, chewing everyone else up in every scene she’s in. Comfortable in her skin. When they meet, Carmilla is someone for Lenore to envy because, to Lenore, Carmilla is the most actualised woman she’s ever met, untethered by society’s laws and propriety. Often found in stages of undress, in nightwear, she’s the object of Lenore’s fascination and curiosity.

Cora is Carmilla’s foil. She is a youthful socialite from London and seemingly Lenore’s only female friend before Carmilla arrives. She seems to breeze through her life. Lenore believes that her youth and station afford her everything she has. Her youth is the subject of Lenore’s envy, and that poisons their friendship. Cora is submissive to Henry’s authority (as a man) throughout their scenes together. It’s later revealed that Henry has confided a secret to Cora and not to Lenore. This makes Lenore suspicious that they are having an affair, which is only compounded when Cora is wearing a necklace that Lenore thought was intended for her.

Henry, what a dick. Sorry—horrible man. He exudes the image of a perfect husband, taking care of his wife if she isn’t feeling well. Kissing her sweetly. However, as soon as they leave London, his frustrations with their falling marriage become apparent. He accuses Lenore of hysteria when she begins to fail at performing what’s expected of her as his wife: demure and dutiful.

Aunt Daphne is only seen through Lenore’s perspective and only seen through the lens of a flashback, so we don’t get to know her as a person devoid of her position as Lenore’s aunt. We are given biased opinions of her. An old curmudgeon.

Themes

Grief is prominent throughout the whole book, and it manifests in various ways. Very early on, we discover that Lenore is an orphan, and she is the sole survivor of a carriage accident where both of her parents die. It feels like a shroud that follows her through the rest of her life. Grief pervades every Aunt Daphne scene. Young Lenore resents and mourns the fact that her life will never be the same following her parents’ death.

Aunt Daphne also has her own grief to deal with. Society has forgotten her, an old woman. She spends her days people watching from her window and making barbs and cutting remarks. Lenore has lost her childhood and must now navigate this woman that is quick to anger.

Lenore resents her aunt for the woman she might become if she doesn’t escape, and Aunt Daphne resents Lenore’s youth. Bitterness sours their relationship. Lenore curates her image with dated guidance to find herself a husband.

Which leads us to our next theme.

Female oppression is a vice around Lenore’s neck. She claws her way out of possible spinsterhood to step into a restrictive marriage to Henry, a fact that is not lost on her either. ‘[Henry]…watched each girl like cattle at auction.’ Henry has always been ambitious, and women, including Lenore, have always been a means to an end. A tool to wield rather than a wife to love. Proximity to an upward rank in society: Lenore might not have her parents’ money, but she has their name and blue blood.

Once they arrive at Nethershaw, Lenore takes it upon herself to oversee the renovation of the house. There are countless passages of imagery given to the rotting house which symbolizes her fruitless marriage, her lack of self and Henry slowly poisoning her to death.

There are also close calls to Lenore becoming the victim of domestic violence. When she questions Henry’s welfare practices at the steelworks, he is enraged. ‘…Henry is out of his chair and standing over me, body vibrating as he holds himself back from whatever it is that his anger wants him to do to me.’ Violence from men is to be endured. The fact he’s leashing himself from doing anything is scary – a real threat. In the same sentence, the way his anger is separated from him as a person, absolving him of the possible blame.

On the same page, Lenore also says, ‘I should be better practised at this by now.’ The absolution reinforced here. But she code-switches to keep him from lashing out, returning to her demure state of dutiful wife so she can avoid violence.

Carmilla is a modern woman and upends everything in Lenore’s life, questioning why Lenore adheres to her husband’s will. On page 92, ‘Carmilla…sips a little more wine. “And young women? What of their ambitions?”’ Which is then followed by on page 94, ‘“For what do you hunger?”’ This encapsulates everything. What does Lenore want? Carmilla is questioning Lenore whether she can actually exact her wants and desires.

Throughout the book, Lenore has to be the one to discover how to break out of her self-imposed prison. She begs Carmilla to aid her but is met with the reply, on page 185, “I am a mirror to those who need it. To those who hunger but deny themselves.” This is the thesis for the entire book. Carmilla is the lens in which Lenore must look at herself to enact on her desires, curiosity, exploration, ambition. Hunger.

Early on in the book, there are various pages where Lenore yearns for Carmilla without realising the sapphic nature of what’s she’s saying. On page 68, ‘Carmilla holds an allure, like ghosting a finger around the edge of a flame: the temptation, the beauty, and the anticipation of pain.’ Followed by on page 70, ‘I have chosen Carmilla, and I will have her.’ Then followed by on page 71, ‘An image… the night dress slipping off her shoulder, low enough that the soft swell of her breast is revealed…’ This kind of sapphic lust is an experience that is outside the strict heteronormativity of the Victorian era. The first stages of Lenore’s discovery about herself manifest on page 82: ‘I dread her, and I crave her.‘ She’s caught between her propriety and her desires.

On page 224, Carmilla says, “Wanting is not selfish, Lenore.” Everything that follows in their argument is Carmilla trying to goad Lenore into being selfish and wanting and hungry. Their anger is a true emotion – no falsehoods, hiding behind expectation. That twists into sexual desire.

It’s then that Carmilla bites Lenore, which is the closest thing we get to conscious vampirism.

It’s the climax of the book because from then on, Lenore’s rose-coloured glasses are off. And she’s concerned with the self for the first time, without her focus being survival. Queerness being coupled with vampirism is so perfect because both things are being used as vehicles of freedom and exploration.

It’s not pretty sex either: there’s a rawness and a carnality there. Lenore is able to hunger for something that’s usually denied to women of the time—the orgasm. It’s a moment of empowerment.

Part Two of the book is called It is The Living. Lenore’s petite mort has literally led to her rebirth and acknowledging her own hunger, her ambition.

On the following page when Carmilla has disappeared after their coupling, page 246, ‘…What a strange, cruel gift she has given me: to truly know myself, to know pleasure, to know freedom – and to wake and find myself in Hell.’ Lenore has to be the one to break herself out.

When they do reunite, their reunion is a mixture of desperate want and the sharp reminder of abandonment. This abandonment leads to Lenore distrusting Carmilla for leaving her. Carmilla, being an ageless and ancient creature, she seems to be all-knowing of Lenore’s life like a vampiric fairy godmother. But Lenore needed to discover for herself her own ambition and hunger.

Interestingly, for Lenore to complete her transformation into a self-actualised woman like Carmilla, she makes many references to femininity or how she experiences femininity to be monstrous. On page 300, Lenore ponders: ‘What is a monster but a creature of agency?’ Shoutout to my favourite line of the book! Monsters are feared because they are able to do whatever they like. They aren’t tied to societal standards and thereby the control of men. Lenore can finally act.

TAKEWAWAYS

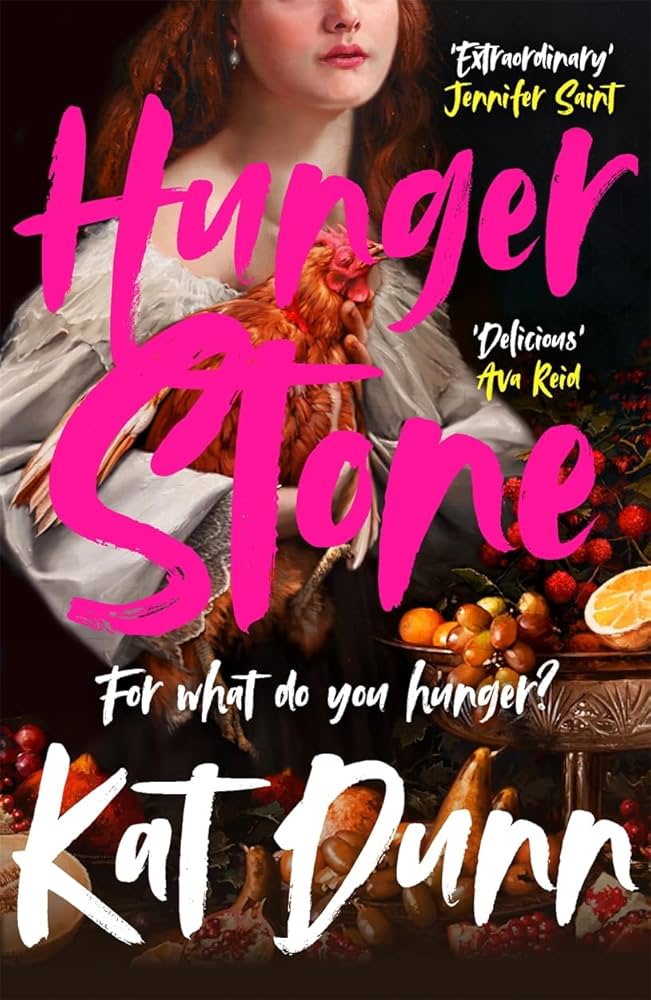

The cover and jacket’s theming are lavish and decadent, harkening to the opulence of Renaissance paintings. The cover depicts an abundance of food, almost too gluttonous for one person to consume. The woman on the cover is draped in gorgeous white, but her throat is exposed and she has no identity beyond her mouth. There’s a sensuality in her pose, offering the spectator her bare shoulder. She holds a chicken, possibly moments before its sacrificed for the table. The bright pink of the font links to the feminine aspects of the novel and cohesively works with the colours of the food in the image.

I need to shout out the quotes that have stayed with me since finishing the book that I’ve not previously mentioned. On page 47: ‘There is bloodshed already.’ One of many blunt, staccato sentences that linger with the reader and have great tempo and impact. Phrasing is visceral and infers so much in so little; and on page 57, ‘There is a sense of vertigo. And the drop below.’ It’s a great use of formatting on page, tempo and gravitas. There’s a prolonged sense of dread.

Between info-dumps, we’re either walking in caves or hanging out with one of the Boring Boys.

CRITICISMS

One of the devices used throughout the book is the use of flashbacks to infer context for Lenore’s motivations. These flashbacks are largely successful, with the particular reveal that Henry is indebted to Lenore because he accidentally killed someone while on a hunt and Lenore helped him in covering it up. However, I found myself wanting the later Aunt Daphne flashbacks to hurry up because she isn’t the most likeable character. An old bat. But that’s the point. The latter Aunt Daphne sections only really offer melancholy, whereas the passages before are vessels so that we know what Lenore wanted to escape by marrying Henry. Now there is only sad, lonely womanhood. Aged womanhood. They are mirrors to the future if Lenore chooses not to take risks.

Another criticism I have is that, about two-thirds into the book, there is a repetitive sentiment that Lenore wants more for herself. Pages, 254, 262 and 275 all infer that she has new needs that she is unable to satiate within her current confines and needs to escape – it does feel like more meditations than taking action at times.

My final criticism – which admittedly isn’t even a criticism as such – is that when Lenore finally kills Henry, on page 372, ‘His throat is there before me, a column of white and blue veins. I stretch my jaw and bite. Teeth sinking into the meat of his neck. The crunch of larynx and spurt of arterial blood into my mouth.’ It’s visceral and grotesque, but I wanted it to be longer because I craved the catharsis as much as Lenore did.

CONCLUSION

Lenore and the reader then arrive full circle at the end of the book with the line, ‘It ends with blood’, having the book started with blood. Now, Lenore is unbound by the confines of her oppressive marriage and has exacted her revenge. The line at the beginning of the book, ‘I was good for nothing but blood.’ Implied that Lenore would possibly be the one to die after succumbing to Carmilla’s vampiric tendencies. To be a woman is to be monstrous. With Henry’s death, Lenore can turn a new page, be reborn and finally live for herself. A retelling of Carmilla is a perfect backdrop to explore the themes previously mentioned as vampirism and queerness have a long history of being used to subvert norms of society.

Vampirism is one of my favourite allegories for romance and love due to the intimacy required to enact such connection.

I read this book between June and July 2024 and quickly devoured most of it, but interestingly I forced myself to slow down as I did not want it to end. I put off finishing it because I became so wrapped up in Lenore and understood her so completely. I knew from the opening chapter that this book was going to consume me for a very long time after I closed the final page. And sure enough, it still does. It’s one of those books that leaves you, you don’t leave it. To end the book was to grieve its loss, grieve the fact that I had finished it. Hungerstone has joined my (very few) five-star reads and it will remain there.

It oozes with gothic. There’s a romance to it that lingers. It’s bittersweet, with its melancholy and catharsis. It sinks its maws into you and refuses to let go.

This post contains affiliate links which earn me a commission at no additional cost to you.

One thought on “Guest Book Review | Hungerstone”